“The Tougaloo Nine and the Fight for Equal Access to Public Libraries, 1961.” When most people think of civil rights sit-ins, they envision lunch counters and picket lines. Fewer remember the quiet, deliberate courage of nine students from Tougaloo College who walked into the whites-only Jackson Public Library on March 27, 1961, and read. That “read-in” — which led to arrests, courtroom battles, and national reverberations — sits at the intersection of two essentials: the fight for civil rights and the fight for equal education. This post tells the story of the Tougaloo Nine, explains why libraries mattered, and argues that access to books and information was as central to the movement as voting rights and public accommodations. BlackPast.orgZinn Education Project

Why a Library? Why Tougaloo College Students?

The choice of a public library as the protest site was deliberate. Libraries were (and are) public institutions funded by taxpayers — white and Black alike — yet access was systematically denied to African Americans across the Jim Crow South. For students and educators at historically Black colleges like Tougaloo, the denial of access to comprehensive library collections was not an abstract injustice: it directly limited their ability to research, study, and compete on equal footing in classrooms and professional life. Tougaloo College was a small, fiercely intellectual hub of activism; its students trained in nonviolent resistance saw the library as a strategic target precisely because the denial was paid for with the taxes of the very people banned from entry. BlackPast.orgAquila Digital Community

Tougaloo students were not lone agitators. They were part of organized youth activism locally connected to the NAACP Youth Council and guided by experienced organizers. Their choice made a moral argument: if public funds create a public service, then public access must follow. That principle would become a key lesson of the movement — that civil rights were not merely about social courtesy but about structural access to public resources and education. BlackPast.orgZinn Education Project

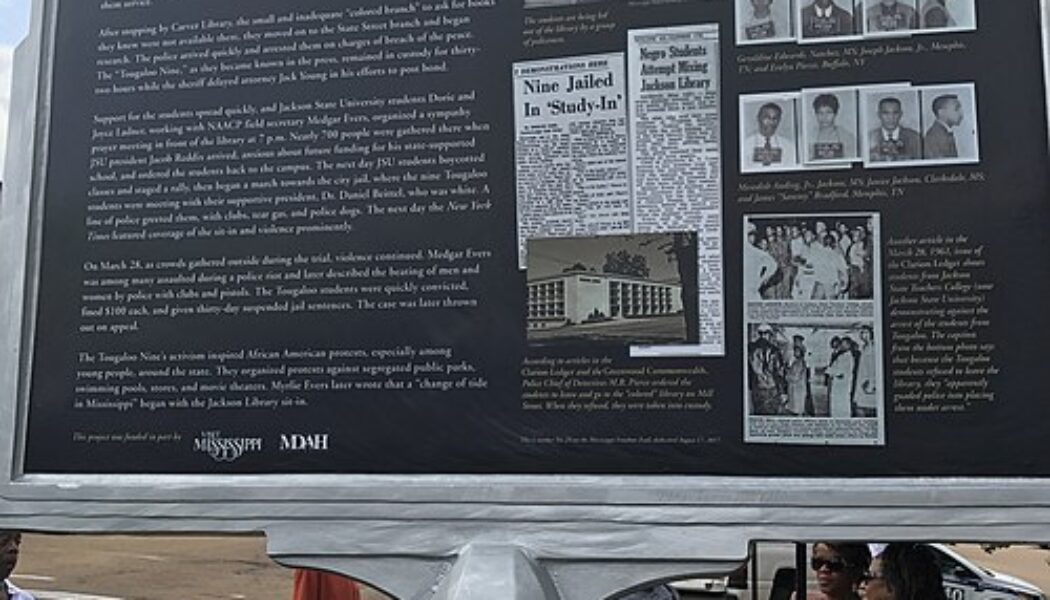

Meet the Nine: Names and Roles

The Tougaloo Nine were undergraduate students who volunteered and trained for a nonviolent “read-in.” Their names are recorded in civil rights histories and local archives:

- Meredith C. Anding Jr.

- James C. (Sammy) Bradford

- Alfred Lee Cook

- Geraldine Edwards (later Hollis)

- Janice Jackson

- Joseph Jackson Jr.

- Albert Earl Lassiter

- Evelyn Pierce

- Ethel Sawyer

These young people were not anonymous footnotes; they were organizers, scholars, and citizens who understood the connection between access and opportunity. Many went on to careers in education, social work, and activism — and their bravery carved space for others to learn. BlackPast.orgAquila Digital Community

The story of the Tougaloo Nine reminds us that civil rights is not only about the visible stages of protest but about quiet access: the ability to open a book, to consult a periodical, to complete research without barriers. The simple act of reading in a public place became a radical claim: knowledge must be public, and public resources must be shared. That claim is still unfinished work today. If the movement taught anything, it’s that small acts of disciplined courage — students sitting down and reading — can bend institutions toward justice.

March 27, 1961: The Read-In and Arrests

The action followed a pattern that had started to spread across the South: test segregated public spaces, refuse to vacate, and use arrest to dramatize the injustice. The group first checked the Carver (the Black public library) for materials they needed for class and discovered the volumes and resources were insufficient. They then entered the main Jackson Public Library, sat quietly, and read. Library staff called the police. When the students refused to leave, they were arrested and charged with breach of the peace. The next day, they were released on bond, and within days, the arrests sparked protests, rallies, and national attention. Zinn Education ProjectAquila Digital Community

The charge of “breach of the peace” — a catchall used to criminalize civil-rights protesters — demonstrates how legal systems were weaponized to preserve segregation. What made the Tougaloo Nine’s action potent was its clarity: they were not attempting to loot or to disrupt; they were asking to read books that Black students needed to complete coursework and pursue higher learning. The optics of peaceful students reading while being led away by police hands were ethically jarring to observers and clarified the stakes: knowledge denied is opportunity denied. Aquila Digital Community

What Happened Afterward: Court, Community, and Consequences

The Tougaloo Nine stood trial and received fines and suspended sentences — but criminal penalties were only part of the fallout. Locally, their arrests ignited widespread community protest that included pickets, rallies, and a “No Buying” boycott against discriminatory businesses. Nationally, the action forced library professionals and associations to confront segregation in their ranks.

In 1962, the American Library Association (ALA) moved to adopt policies insisting that membership and chapter status could not be racially exclusive. Several Southern state library associations objected; Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi at one point withdrew from the ALA over the issue. Still, that institutional pressure — prompted in part by the kind of visibility generated by the Tougaloo Nine — pushed desegregation forward inside the professional field of librarianship. American Library AssociationBOOK RIOT

Locally in Jackson, the action contributed to the eventual desegregation of some library services. More importantly, it codified a moral argument used across the movement: public institutions created with everyone’s money should be open to everyone’s use. That logic would be used to fight for integrated schools, parks, buses, and polling places. BlackPast.orgDigital Public Library of America

Libraries as Battlegrounds for Education

Civil-rights historians increasingly stress that the movement was as much about knowledge and education as it was about physical space. Public libraries provide more than books: they provide access to periodicals, research materials, records, and quiet study space — all of which expand a student’s intellectual horizons and ability to succeed academically. When a community is barred from its main repository of information, that community’s students and professionals are set back structurally. The Tougaloo Nine made this practical and visible. BlackPast.orgDigital Public Library of America

Consider the academic cascade caused by unequal library access: fewer books mean fewer references for papers; fewer references mean less robust scholarship; less scholarship reduces competitiveness for graduate school, jobs, and research grants. Denying library access is a form of educational redlining. The Tougaloo Nine’s read-in framed libraries as critical infrastructure in the education ecosystem — infrastructure that deserved protection by civil-rights law and moral force. Aquila Digital Community

Training, Mentorship, and the Role of Organizers

The Tougaloo Nine didn’t act in isolation. They were trained in techniques of nonviolent resistance by local and regional organizers, including NAACP members and civil-rights leaders who worked in Mississippi in the early 1960s. This training included discipline under provocation, legal preparation, and community outreach plans. The success of the movement’s tactics — sit-ins, read-ins, freedom rides, and voter drives — leaned heavily on disciplined training and strategic choice of targets, which the Tougaloo students exemplified. Zinn Education ProjectBlackPast.org

Mentorship mattered not just tactically but emotionally. When young students faced hostile police and an indifferent judicial system, the presence of seasoned organizers and supportive community networks amplified their courage and reduced the chance that arrests would produce despondency rather than organized resistance. The Tougaloo Nine benefited from a culture at Tougaloo College that combined academic rigor with activist training. Aquila Digital Community

The Moral Argument: Taxpayer Rights and Public Resources

A powerful rhetorical move of the Tougaloo action was the appeal to fairness via the taxpayer frame: “The library is paid for by my taxes; why can’t I use it?” This argument reframed segregation from being a local social custom into a matter of public accountability. If a city collects funds from all citizens and builds facilities for public use, exclusion of any group is a theft of public benefit and a denial of civic equality. That framing helped persuade some moderates and created pressure on professional bodies such as the ALA to take a stand. BlackPast.orgAmerican Library Association

Framing the issue this way moved the debate from abstract moral appeals to concrete economic and administrative injustice. It engaged people who might not have been touched by appeals to rights alone but could understand being excluded from a service that they had helped pay for. This strategy is one reason the library sit-in resonated beyond the immediate neighborhood. Zinn Education Project

How the Tougaloo Nine Changed Library Policy and Professional Ethics

The Tougaloo Nine’s action was an inflection point for the library profession. In the early 1960s the American Library Association faced pressure to address segregation within public and professional settings. The ALA’s subsequent moves — including statements that institutional membership could not be racially exclusive — were shaped by case studies like Jackson’s. Southern library agencies that clung to segregated practices faced ostracism, and some withdrew from the ALA in protest. Over time, the profession’s standards shifted toward inclusivity and intellectual freedom, in part because activists forced the policy question into the open. American Library AssociationBOOK RIOT

This was not immediate nor universal: resistance and retrenchment persisted in many places. But the public spectacle of students being arrested for reading made it professionally embarrassing to remain silent. The ALA’s stance eventually helped normalize integration in a field that had been slow to confront Jim Crow. Modern library apologias and reparative statements — official expressions of regret for libraries’ roles in segregation — can trace part of their lineage back to actions like the Tougaloo read-in. American Libraries Magazine

Education, Access, and the Long Shadow

If you map the arc from the Tougaloo Nine to later civil-rights victories, you see a throughline: expanding access to information and institutions is foundational to expanding political and economic power. A student denied research materials cannot produce scholarship or qualify for advanced programs. A community denied library access loses civic literacy tools such as voter guides and legal references. The movement’s successes in desegregating public spaces thus had ripple effects for education, civic participation, and social mobility. BlackPast.orgDigital Public Library of America

The Tougaloo action also modeled a tactic: target public institutions funded by all citizens to expose hypocrisy and seek structural remedies. It’s a lesson activists return to today, whether arguing for equitable broadband, equal school funding, or open access to public records. The precedent is clear: when public infrastructure is exclusive, activists can highlight the contradiction and demand change. Aquila Digital Community

Voices from the Movement: Remembering Courage

Contemporaries and later historians have credited the Tougaloo Nine with helping shift momentum in Mississippi. Myrlie Evers and others noted that the library sit-ins helped change the tide in a state hostile to desegregation. Local rallies after the arrests drew thousands and showed the community’s capacity for organized resistance. These human responses — the chants, the picket signs, the jail cells — are essential to understanding how a modest read-in turned into a community cause. CRM VetAquila Digital Community

Those directly involved later told stories about the fear and exhilaration of walking into a segregated building with a pile of books and the quiet dignity of reading while being watched by police. The photographs and mugshots that circulated afterward put faces to the moral argument and made it harder for the broader public to ignore that plain reading had become criminalized. That visibility was part of the movement’s power.

Lessons for Today: Libraries, Equity, and Activism

What does the Tougaloo Nine story teach a contemporary reader?

- Public institutions are strategic targets. If structural inequality is maintained by rules at the institutional level, then winning equal access to those institutions advances equality.

- Knowledge access is economic access. Libraries provide resources that affect career and educational outcomes; equitable library access is a pathway to social mobility.

- Professional bodies matter. Pressure on organizations like the ALA can produce policy changes that ripple outward. Professional ethics and accreditation can be levers for social change. American Library Association

Today’s fights — for affordable internet, school funding, community archives, and culturally relevant collections — are all descendants of the Tougaloo Nine’s insistence that a public library be open to all taxpayers. The method also endures: disciplined nonviolence, legal navigation, community organizing, and strategic framing. Aquila Digital Community